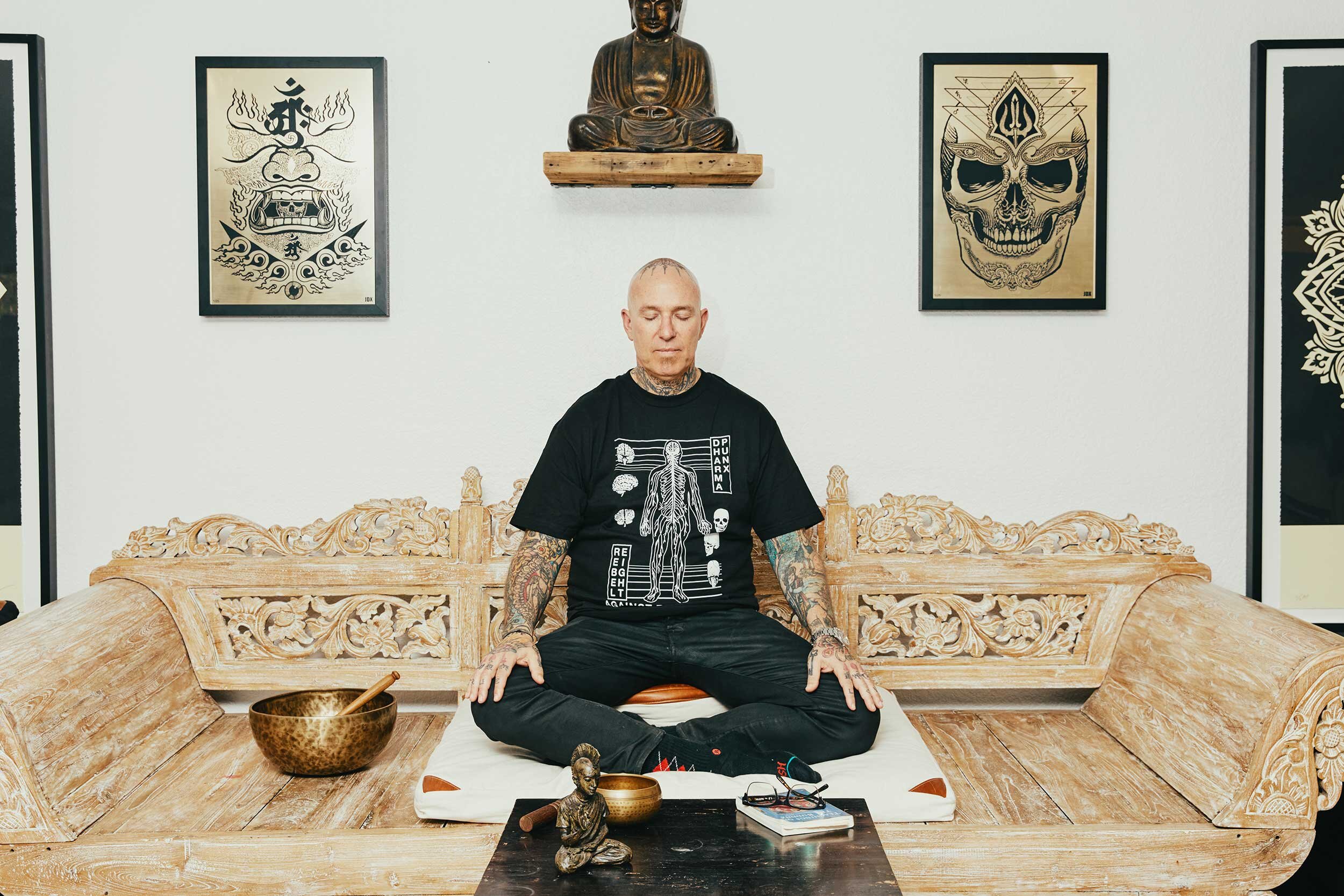

Finding Freedom | Breaking the Addiction; Against The Stream: A Buddhist Manual for Spiritual Revolutionaries

Read Part ONE and TWO of Against The Stream: A Buddhist Manual for Spiritual Revolutionaries here.

FINDING FREEDOM | BREAKING THE ADDICTION

Against The Stream: A Buddhist Manual for Spiritual Revolutionaries

One of the problems we face as spiritual revolutionaries is that we get comfortable

Even though we don’t always like what we are experiencing, it is familiar. We don’t like the dissatisfaction, the suffering, and the difficulty of life. We wish it were different, but we are so comfortable in it. It is all we have ever known. Like a child who is abused by his or her parents—a child who screams for the familiar “comfort” of those parents as they’re being hauled off by the police for beating him to a pulp—most of the time we would rather stay with the familiar than face the unknown, even when what’s familiar is our suffering. We are so used to our confusion that when the choice for freedom comes, we think, No way—it’s too hard. Because the unknown is too scary, we go through our lives repeating patterns of thought and action even when they bring us pain.

We can also get lost in delusional philosophies that explain the difficulties of life. We like such philosophies because, being scared, we feel we have to have the right answer all the time. Many of the world’s religious traditions are a direct reaction to the confusion and difficulty of life. It is difficult to rest in not knowing, so we create the delusion of knowledge. Humans devise creation myths, psychological theories, cultural norms, political beliefs, and religions, all in a vain attempt to appease or control their core feelings of insecurity and not knowing.

What Buddhism offers that differs from most other theories is a direct experience of what is true

Buddhism doesn’t ask for blind faith or belief; it offers a practical path to walk

We cannot find freedom by thinking about it with an untrained mind. The untrained mind is not trustworthy; it is filled with greed, hatred, and delusion. Only the mind trained in mindfulness, friendliness, and investigation can directly experience the freedom from suffering that will satisfy the natural longing for security. This is the wisdom of insecurity.

In relationships we can often see the manifestation of this fear of the unknown. We go through our lives attached to our familiar suffering by getting into the same type of unsatisfactory relationship again and again. How many times do we have to fall in love with someone just like Mommy or Daddy before we acknowledge the pattern of seeking love as an attempt to heal an old wound? Does it ever really work? With mindful investigation, we can see for ourselves what our patterns and habitual reactions are—and from that place of true knowledge, we can then begin to choose our responses, actions, and partners more wisely.

Life doesn’t have to be so unsatisfactory. This is the good news: there is a cause to our confusion and suffering—it is our relationship to craving—and that cause can be altered to bring about a different effect. Notice that I don’t say it’s craving itself that’s the problem. That’s just a natural phenomenon of the conditioned heart-mind. No, the problem lies in our addiction to satisfying the craving. We all experience craving. When we have a pleasant experience, we crave more of it—we wish for it to increase or at least to last. When we have an unpleasant experience, we crave for it to go away. We feel the need to escape from pain, to destroy it and to replace it with pleasure. We are addicted to pleasure, in part because we confuse pleasure with happiness. We would all say that deep down, all we want is to be happy. Yet we don’t have a realistic understanding of what happiness really is. Happiness is closer to the experience of acceptance and contentment than it is to pleasure. True happiness exists as the spacious and compassionate heart’s willingness to feel whatever is present.

Though pleasure is in no way the enemy in our search for happiness, it comes and goes. When it’s here we tend to grasp at it; when it’s gone we want more. That addiction is the untrained heart-mind’s natural reaction to anything pleasurable. This is clear in the Buddha’s second noble truth: the cause of suffering is craving for pleasure.

Though we speak of, for example, drug addicts, what we are really addicted to isn’t substances—drugs or sex or food or alcohol—but our own minds. We are addicted to that part of the mind that craves, that says we must satisfy this desire or that. Even in twelve-step recovery programs it is said that the drugs and alcohol are only a symptom of an internal imbalance. That’s why I said earlier that our relationship to craving is the problem, not some substance itself. And we pay the price for that relationship to craving.

Our suffering in life is due to our addiction to our thoughts and desires

We wander through life constantly craving more of the pleasant stuff and less of the unpleasant

Against The Stream Buddhist Meditation Center, Venice, California

This is the place where spiritual practice as a form of rebellion comes in. My own experience, and the Buddha’s “against the stream” principle, tells me that that it’s counterinstinctual: it goes against our very human instincts to accept pain and not chase pleasure. It is a veritable internal battle, because breaking the addiction to our knee-jerk satisfaction of craving goes against our natural human tendencies. When life is uncomfortable, we naturally want it to change; when life is good, we want things to stay as they are. It goes against our nature to stop trying to satisfy our craving, to allow the craving to be there without reacting to it. Few of us have the courage to accept pain as pain and pleasure as pleasure, and to find the place of peace and serenity that accepts both pain and pleasure as impermanent and ultimately impersonal. But our confusion may also go beyond the courage to train the mind. Other than Buddhism, few teachings even allow for the possibility of this kind of freedom.

Most of us have a fantasy of spiritual awakening as being purely pleasurable all the time. This fits right in with our craving for pleasure, but also with the creation of more suffering. The awakening of the Buddha within each one of us is the experience of non-suffering. Not suffering could be considered blissful in comparison to suffering, but that does not mean that it is pleasurable all of the time. We have to let go of our fantasy of unending pleasure and the craving for a pain-free existence. That is not the kind of spiritual awakening that the Buddhist path of rebellion offers.

The important question then is, “How do we break this addiction?”

How do we loosen our identification with craving and the satisfying of our desires? How do we break our addiction to our minds? How do we get free?

The untrained mind, the natural state of human consciousness, has very little free will. We talk easily about free will, about freedom of choice, but I propose that without training the mind, we don’t truly have the ability to choose. We are actually slaves to, or addicted to, the dictates of the past, of our conditioning—of our karma, or past actions. The Buddha outlines this clearly and in great detail in the teachings of dependent origination. This is Buddhist psychology. As we saw in the earlier discussion of understanding, the Buddha explains how we create suffering for ourselves, how we tend to be victims of the past, and how we don’t have free will unless we bring awareness and attention to this process of dependent origination. The short version of this principle is that we have the ability to break our habitual addictive reactions through close attention to the mind and body.

The foundational practice is paying attention to our mind, our body, and our present-time experience. It is hard to pay attention, because we have to face some ugly truths and tolerate some discomfort. One ugly truth may be that our fear, lust, or anger is all we see in the beginning. Since the mind does not easily pay attention to the present, effort is necessary. The mind, which is all over the place from one moment to the next, has to be trained. The Buddha said the mind was like a monkey swinging in a tree from one branch to the next. Yes, that is what the mind does: it swings from one thought to the next, from the future to the past, from planning to remembering, from self-hatred to grandiosity. To get some stability, we need the intentional effort of repeatedly bringing the attention back, of paying attention to the present-time experience of breath and body, over and over.

In fact, we are paying attention to something all of the time, though it may be a fantasy in our mind, perhaps a daydream about a more pleasant future. Through redirecting our attention to the present moment, to the simple reality of our breath and body, and through investigating the feeling tone of each experience, we open ourselves to the possibility of freedom.

Right now there is the experience of sitting here reading this book. Is it pleasant or unpleasant? Are you meeting the discomfort in your body with aversion or compassion?

Bringing awareness to the feeling tone in this moment allows us to relax and release the aversion. Our habitual tendency, when there is discomfort, is to push it away, but the aversion to that discomfort seems to make it grow bigger, and pretty soon we begin squirming around or we feel that we have to run out of the room because sitting still is a pain in the ass.

Awareness of the desire for things to be other than the way they are is key. Thus the first step in breaking the addiction is acknowledging the unsatisfactory nature of both pleasure and pain. We do this by being vigilant toward and aware of the presence of dissatisfaction, the desire for things to be different. Yet we also need to pay attention to moments of ease and well-being, the experience of nonattachment, when the mind is free from suffering. We are usually hyper-vigilant when something is uncomfortable, yet when it is pleasurable or peaceful we often pay no attention, except perhaps to think about how we are going to get more of that pleasure.

Awareness of the lack of satisfaction and of the craving for things to be different allows us to take the next step toward freedom. We can relax the clinging of the mind and body and simply accept that we feel a craving for more or less of something. We can ask ourselves, “Can I accept this one moment at a time? Can I acknowledge that this is the way it is, and though I want things to be different, can I let go of that aversion and let things be the way they are?”

It is important to acknowledge this process as it is going on by investigating it and acknowledging our feelings of craving. Our conditioned tendency is to push or pull or grasp or run. The inner rebellion calls us to the practice of letting go or letting be. From the awareness of grasping or aversion comes the possibility of letting it go. With the trained mind, we can (at least at times) just release our mental or physical grip. Because all things that have arisen will pass, that act of letting go will allow the experience to pass. Letting be is similar to letting go: it means letting the experience (and all the feelings it engenders) be present the way that it is, accepting the experience as unsatisfactory, impermanent, and impersonal.

I often find that I am not so good at internally just letting it go or letting it be, but with time I have become able to tolerate unpleasantness without externalizing it and acting on it. For example, I don’t have to say the angry words; I still experience the anger or fear, but I can pause and respond with compassion rather than react with angst.

The Buddha suggests that once we have acknowledged our clinging or aversion, if we can’t easily let it go, we should try redirecting our attention to something else, to another place in the body that is not painful. For example, during meditation if there is pain in your left knee and you feel the aversion to it but can’t accept or tolerate it, redirect your attention somewhere else; try, for example, bringing the attention back to the breath.

Another level of Buddhist practice that addresses craving is inquiry

We can investigate what is going on. What is underneath this desire for more or less? What is motivating or fueling this aversion? Why is this thought pattern being played over and over again?

When I really start to investigate my aversion, anger, or lust, I almost always find that what is fueling it underneath is fear—a base-level fear that I’m not going to get what I want or I’m going to lose what I have. Sometimes it even manifests as a fear that I won’t be able to tolerate the fear.

I’m not alone in this, I think. Underneath our ego and anger and lust is often the insecurity of fear, which we find when we investigate. Once we recognize it as fear, we can reflect on the fact that fear is not an excuse for inaction. We can then take the next breath or other action and learn to live with fear as a constant companion. If we lived our lives taking action only when fear was not at play, we would do very little. I certainly never would have started meditating in the first place or begun to teach. Almost every time I walk into the prison yard to teach a class, some fear arises, but it is not a problem, just an old and familiar companion. In fact, for spiritual revolutionaries, the wisdom of insecurity becomes our greatest teacher.

Another level of inquiry is to look closely at our mind to see who is experiencing this fear. Whose fear is this? Is it mine? Sometimes it becomes clear that the voices of fear are not even our own. We are hearing our parents, teachers, friends, or enemies. We have incorporated those voices into our psyche and have been believing them our whole life, thinking that the feelings and thoughts of fear were somehow personal.

On a deeper level, we investigate what this sense of self is that seems to be the owner of experience. Who is really experiencing all of this craving? It’s really just the mind, isn’t it? Just more impermanent thoughts arising and passing.

If neither letting go nor investigating works, another skillful way to address craving is to attempt to replace it by actively reflecting on love, courage, and kindness. Since negative mind states are still just mind states, we can try to replace them with positive mind states. The loving-kindness meditation practice is designed for this.

Becoming aware of what we are addicted to and becoming committed to getting free from our misidentification with and addiction to our minds, thoughts, and feelings requires a level of renunciation. A level of being honest with ourselves and realizing that we keep doing the same thing over and over, and the outcome is unsatisfactory every time. Part of our work as spiritual revolutionaries is to break the denial of believing that things are going to be different this time. And then beginning to change our inner and outer actions.

Here is a simple story I’ve paraphrased from Portia Nelson’s There’s a Hole in My Sidewalk that points to the process by which these changes are often made. It takes place in five phases or chapters:

A woman is walking down the street and there is a hole in the street and she falls down into it and doesn’t know what happened, and it takes her a long time to get out of that hole.

The next time she walks down the same street, she knows there is a hole there but she is attracted to it, and she gets curious and she falls in again, but it takes her less time to get out.

The next time she walks down the same street, she knows there is a hole there but she is pretty sure she can jump over it, and she tries to jump over but falls in again.

The next time she walks down the same street, she knows the danger but is still curious, so she walks up to the hole and looks in, thinking, “Damn, that’s a deep hole,” but she doesn’t fall into it; this time she carefully walks around it.

Finally, she chooses to walk down a different street, deciding that she won’t walk down the old street anymore because she knows there’s a hole there!

On the path of the spiritual revolutionary, we need to have that level of renunciation—a commitment that we are not going to walk down the inner streets of greed, hatred, and delusion anymore. Of course it isn’t so simple—our habits and grasping are so deep—but it all starts with the intention to change. To find new ways of relating to our mind.

All of this points toward breaking the addiction to pleasure and the aversion to pain. We each have to ask ourselves, What do we really want in our lives, short-term satisfaction of craving or long-term peace of mind and the healing of the heart that will lead to wisdom and compassion?

When we choose the path of wanting long-term peace, freedom, and true happiness in our lives rather than the short-term satisfaction of pleasure and desire, then the effort to train the mind is there. This has been my experience. When I really keep in the forefront that my intention in this life is to be free, then being of service and practicing meditation and doing what I do to get free becomes the only rational decision.

This takes discipline, effort, and a deep commitment. It takes a form of rebellion, both inwardly and outwardly, because we are not only subverting our own conditioning, we are also walking a path that is totally countercultural. The status quo in our world is to be attached to pleasure and to avoid all unpleasant experiences. Our path leads upstream, against the normal human confusions and sufferings.

At times “waking up” can feel isolating at some level. That’s part of the burden of the real revolutionary. On the relative level we may feel separate from the masses, yet as the practice deepens, on the ultimate level we begin to understand the total interdependence and nonseparateness of all beings.

The commitment to waking up takes stamina. Steadfastness and perseverance are a necessity if we are to continue on a long-term spiritual path. I wish I could say that there’s some magical secret to all of this, that this or that is what it takes to persevere, but I have no easy solution. What it feels like to me is grace, which is a very un-Buddhist term. Truth is, I don’t know why some people get on the path and learn to see the ways we create suffering, yet don’t follow through to liberation. It’s a bit like some alcoholics or addicts who get sober and start doing the steps to recover but then can’t stay clean.

Reflecting on my experience, I feel as if it’s been some sort of grace that keeps the fire burning. The craving for freedom has become more intense in me than the craving for pleasure. I have been blessed with the willingness to postpone short-term satisfaction for long-term happiness. And with that has come a willingness to continue no matter how hard it becomes, to persevere no matter how scary or lonely it gets.

It seems that very few people that start this path continue it for more than a few years, just like very few addicts get sober and stay sober. There’s the effort, practice, and commitment of following the path even when you don’t want to do it; but that level is balanced by this other mysterious level, like some sort of grace. From a Buddhist perspective that other level is karma. Our own past actions have dictated that we are on the path and will continue on the path. In order to fully accept that, we have to understand reincarnation. Since I don’t have any recollection of my past lives, I don’t claim to completely understand reincarnation, so I like to think about it as grace. On the other hand, perhaps it is as simple as courage—the courage to begin, to continue, and to complete the task we took birth for.

I want to again acknowledge how scary it can be, on a core level, to think about getting free. Getting free from the reactive tendencies through breaking the addiction to the mind is like going off into the wilderness to a place you’ve never been before. Yet fear is, has been, and perhaps always shall be our constant companion in this revolution. It makes perfect sense that we want to stay attached to our suffering because it is so familiar. Yet may we be the courageous rebels who are willing to defy the mind’s fears and attachments in service of finding a new home in the hinterlands.

Paradoxically, what we most fear is not darkness—we know the darkness all too well; what we are most afraid of is the light. The light of freedom shines from the unknown, undiscovered truths of compassion, kindness, appreciation, forgiveness, and the wisdom to respond with care and understanding to all beings.

But like any arduous journey that feels like it will never end, the Buddhist path has both rewards and a destination. Along the way, as we face our fears and confusion, we begin to realize that the way is perfectly safe and well worth the effort to persevere. It definitely gets less scary the closer we get. And when we make it through the dense forests, we can enjoy the views from a higher elevation on the path.

You may not experience much fear at the outset. Often in early spiritual practice people get a pink-cloud feeling: the way isn’t scary at all, and life feels easier and more pleasant. But to really get free, most of us will have to come up against terror, deep shame, guilt, and fear.

If your spiritual practice is all pleasant all of the time, you are probably not doing it right. And it may be that very few people have the kind of commitment to go through a heartwrenching, dark-night-of-the-soul type of experience. Again, that’s probably why the Buddha described this path as leading against the stream.

It is said that eventually we will understand impermanence so directly that we will see death everywhere. The end of each moment will become so clear that we will know the end of each experience. It may be terrifying to see the truth of constant change and nonstability in that advanced stage of awakening.

The fact is, I don’t know what it would be like to be enlightened because I’m not. I’m still attached to many things. What I do know is that meditation and spiritual practice have lessened the suffering in my life and changed my relationship to craving.

I also know that I am committed to continuing the path no matter how hard it gets or how pleasurable it becomes.

How do we get free? Breaking the Addiction: Dharma Talk & Meditation with Noah Levine

Each week, Noah answers questions from subscribers chats while live.

Join in the conversation on our YouTube Channel.

WE’RE LIVE STREAMING DAILY

Subscribe and Watch Live

Support Against the Stream

YOUR DONATIONS SUPPORT OUR EXPENSES AND ALLOW US TO CONTINUE TO PROVIDE THE BUDDHA’S TEACHINGS.

Against The Stream is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization: All donations are tax deductible. Tax ID 83-4171718